Not Poor Enough for the Data: Inside India’s Way of Measuring Poverty

The Multidimensional Poverty Index misses the reality of everyday hardship. Homes, water, schools, and healthcare may exist on paper but broken systems, debt, and poor quality leave families struggling unseen. See what the data hides

For many years, poverty was measured mainly by income, i.e., how much money a person or household earns. This approach, known as income poverty, uses a poverty line to decide who is poor. While this helps identify those with very low earnings, it only captures one part of people’s lived reality.

Over time, it became clear that poverty is not just about money - several factors like caste, gender, and visible or invisible disabilities, among others, impact a person’s access to good health and resources. A family may earn slightly above the poverty line yet still struggle with malnutrition, unsafe water, lack of schooling, or inadequate housing.

To address these gaps, several other measures emerged.

The Human Development Index (HDI) broadened the perspective by looking at health, education, and standard of living, but it reflected national averages rather than the specific problems households face. The basic needs approach looked at access to essentials like food, shelter, water, and sanitation, but it lacked a clear and consistent way to combine these factors into a single measure.

What is the Multi-dimensional Poverty Index?

The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), developed by the United Nations Development Programme and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, provides a more comprehensive approach to understanding poverty. Instead of looking only at income, MPI considers several basic needs, such as nutrition, education, and living conditions, to recognise that poverty affects many areas of a person’s life simultaneously.

MPI is widely used today because it shows not only how many people are poor but also how deeply they experience poverty. It helps identify the specific challenges households face, such as a lack of clean water or poor housing, which makes it easier for governments and organisations to design targeted solutions. Most importantly, MPI reflects real-life problems that income alone cannot explain, giving a more accurate and humane picture of what it means to live in poverty.

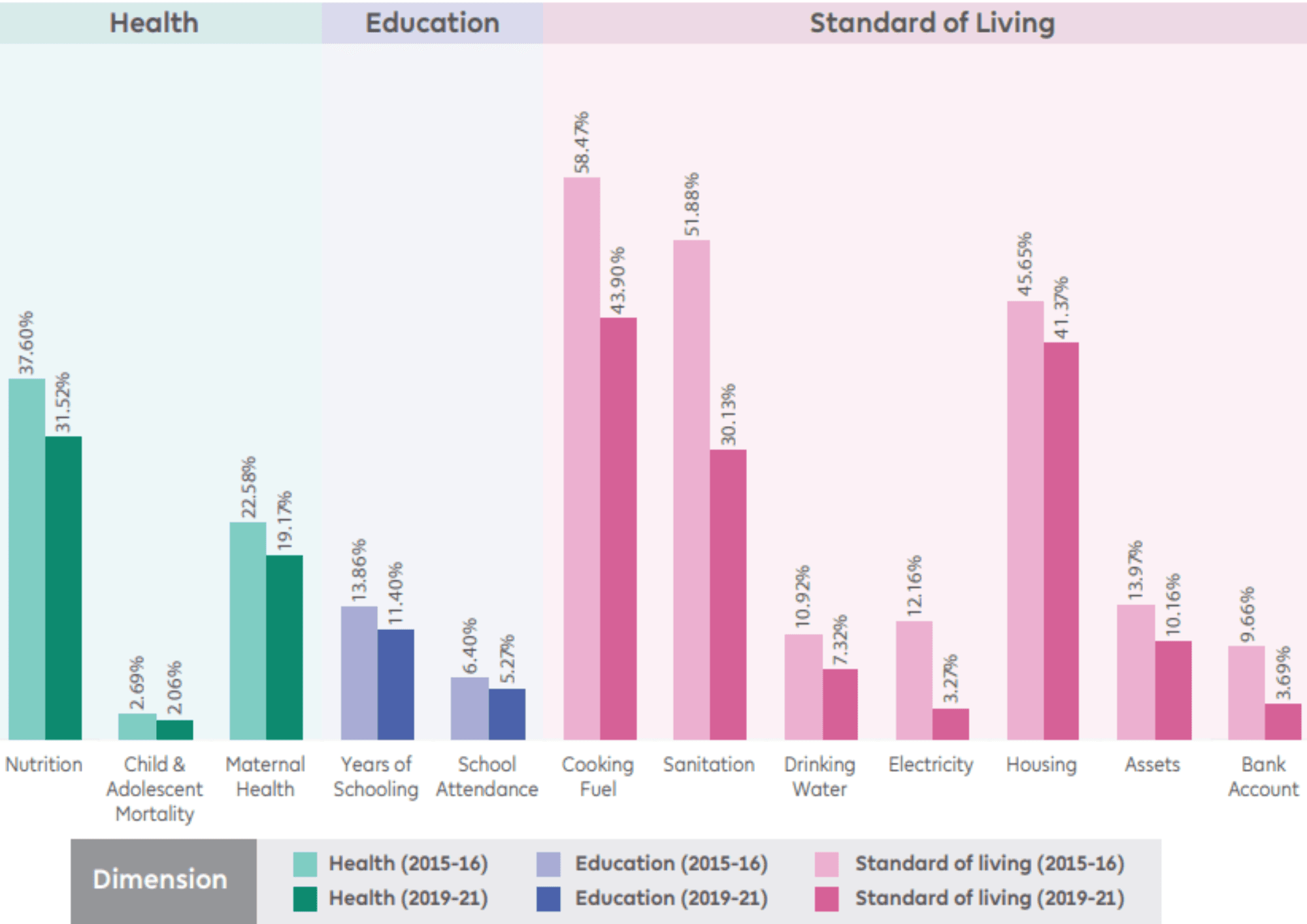

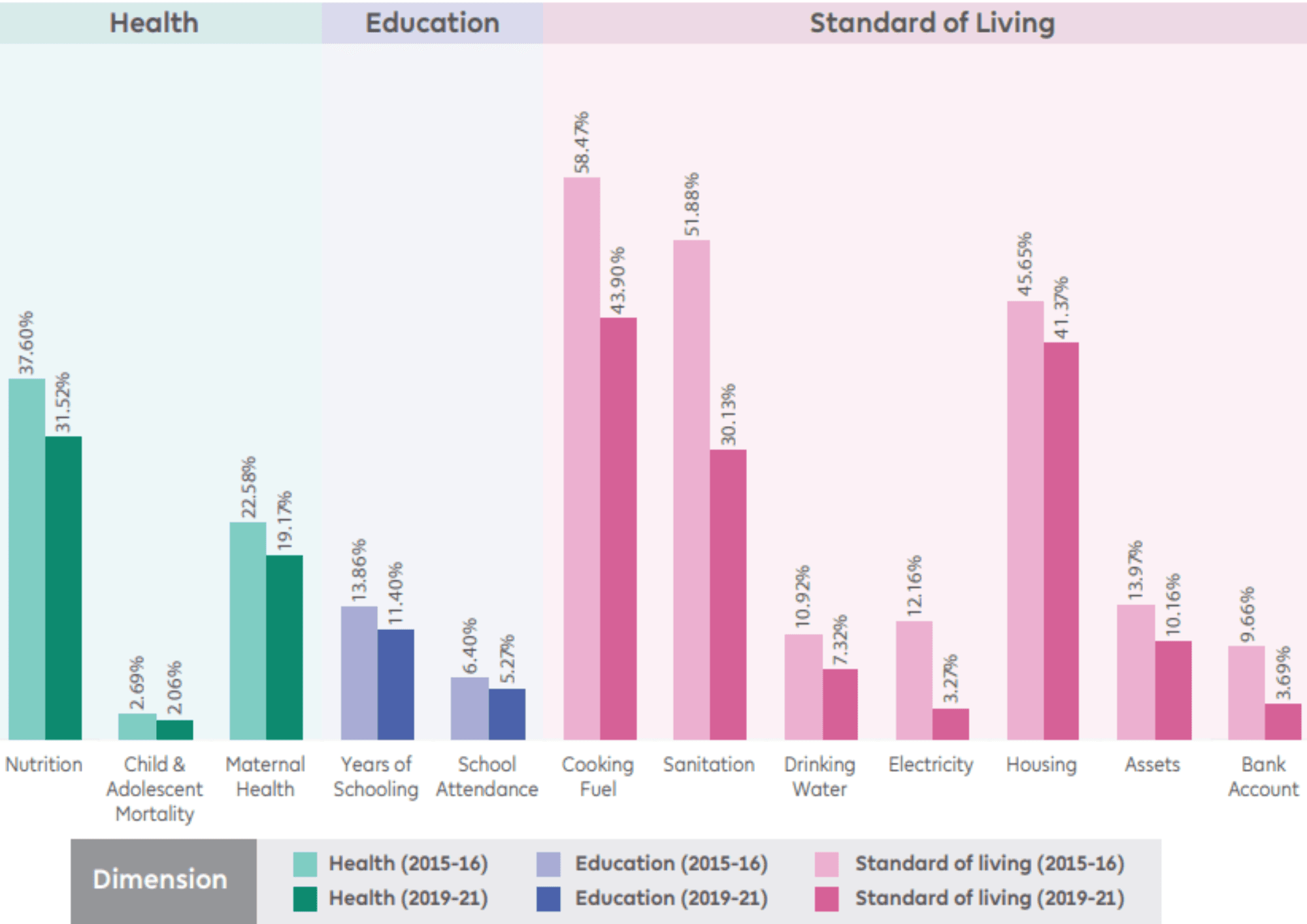

The original global Multidimensional Poverty Index includes 10 indicators across health, education, and living standards. However, India’s national MPI expands this framework to 12 indicators to better reflect the country’s specific development priorities and lived realities. In addition to the global indicators, India includes measures such as maternal health and bank account access, recognising the importance of financial inclusion and safe motherhood in understanding poverty within the Indian context.

The Indian government reports a sharp decline in the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), from 53.8 percent in 2005–06 to 16.4 percent in 2019–21. To assess whether this reduction genuinely reflects conditions on the ground, it is essential to examine how the MPI is constructed and measured.

Using the example of families living in a tribal hamlet in Tamil Nadu, a state where only 2.2 percent of the population is classified as multidimensionally poor, we illustrate how the MPI operates in practice and what it may obscure.

When Malnutrition does not Count

The health indicators in the Multidimensional Poverty Index focus on nutrition and child mortality. While this simplicity might be intentional - designed to enable cross-country comparability and reliance on ‘measurable’ proxies of deprivation - it can overlook important aspects of wellbeing. Nutrition is assessed using Body Mass Index for adults and height-for-age or weight-for-height for children. A household is marked as deprived if even one member is undernourished.

The child in this photograph shows flag hair, a visible clinical sign of protein deficiency caused by repeated periods of food scarcity. Yet, because the child’s height and weight fall within the “normal” range, the MPI would classify them as nutritionally adequate.

When Health is Reduced to Survival

In the Multidimensional Poverty Index, health is partly measured by a single question: has a child in the household died? While child mortality is a grave marker of deprivation, by equating health deprivation with mortality it reduces health to survival alone and overlooks the many conditions shaped by access, care, gender, caste and other social determinants, all of which impact ways people live with illness.

In a time when diabetes, hypertension, cancer, and chronic disability are increasingly common, this narrow lens fails to capture everyday suffering. The MPI does not ask whether families can reach healthcare, afford treatment, or are pushed into debt by illness. By ignoring access, quality, and financial burden, it risks making widespread ill-health and healthcare inequities invisible in the data.

When Maternal Care becomes a Checkbox

India’s national Multidimensional Poverty Index includes antenatal care as an indicator, signalling an important recognition of maternal health. On paper, counting Antenatal Care (ANC) visits suggests monitoring, safety, and access to care during pregnancy.

But the indicator records only whether a minimum number of visits occurred, not whether the care was timely, appropriate, or adequate. During fieldwork, the authors met a household where both a 45-year-old woman and her 22-year-old daughter-in-law had one-year-old children. Although both met the ANC criteria, their pregnancies carried vastly different medical risks.

The indicator did not capture high-risk pregnancies, age-related complications, or access to specialised care. By reducing maternal health to a checklist, the MPI risks hiding deep inequalities in the quality of care women actually receive.

Education Assessment

The education indicators in the Multidimensional Poverty Index examine whether adults have completed at least six years of schooling and whether all school-age children are enrolled and attending school. A household is considered deprived if no adult has reached this basic level of education or if even one child between 6 and 14 years is not in school. These indicators aim to capture barriers to literacy, learning, and future opportunities.

However, these measures focus only on the presence or absence of schooling and do not consider the quality of education received. Completing six years of schooling does not guarantee functional literacy, critical thinking, or skills needed for employment.

Similarly, counting children as “non-deprived” simply because they are enrolled ignores the well-documented challenges within India’s public school system. Many schools operate with shortages of teachers, have overcrowded spaces, or operate with inadequate infrastructure, all of which constrain meaningful learning.

The MPI also does not account for skill development, vocational training, or pathways to employability, leaving critical dimensions unexamined. Gendered dropout patterns and caste-based exclusion also remain invisible in MPI’s education metrics.

As a result, the MPI may overestimate the educational well-being of households while overlooking the deeper structural issues that limit real learning and future livelihood opportunities.

India’s withdrawal from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) survey in 2025 further highlights this concern. PISA assesses the mathematics, reading, and science competencies of students aged 15 years to meet real-life challenges. India last participated in this assessment in 2009, when it placed 73rd among 74 participating countries, ranking just above Kazakhstan.

Since then, India has not participated in the survey citing “cultural disconnect” with the survey. Though the government-run National Achievement Survey (NAS), and the independently conducted Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) surveys assess learning competencies in India, studies have questioned their reliability citing possibility of inflated scores.

When Clean Fuel Exists Only on Paper

The living standards indicators in the Multidimensional Poverty Index assess deprivation based on the type of cooking fuel a household uses. Families relying on firewood, dung, or crop waste are classified as deprived because these fuels produce toxic smoke and harm health.

But this indicator often captures access, not use. Many households receive a subsidised LPG connection, yet the high cost of refilling cylinders forces many of them to continue fuel stacking - using LPG occasionally while relying primarily on firewood or dung for daily cooking. As a result, on paper or during the survey, they appear “non-deprived” and having clean cooking fuel. In reality, they continue to inhale smoke every day, an everyday hardship that disappears from the data.

When Sanitation is Counted, not Used

Sanitation is a key living standards indicator in the Multidimensional Poverty Index. Households are considered deprived if they practice open defecation, share toilets, or lack systems that safely manage waste, reflecting concerns of hygiene, disease, privacy, and dignity.

Yet the indicator often measures construction, not functionality. Toilets built under Swachh Bharat Abhiyan may exist on paper but remain unusable due to lack of water, poor maintenance, or alternative use as storage spaces. Despite this, such households are classified as non-deprived, allowing the reality of unsafe sanitation to remain invisible in the data.

When Electricity is Counted, not Delivered

In the Multidimensional Poverty Index, access to electricity is measured simply by whether a household is connected to a power source. Lack of electricity affects children’s ability to study, limits access to information, and compromises safety and daily life.

In the village the authors visited, electricity was officially available through a solar panel installed using corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds. Over time, the system stopped working. The CSR funding covered installation but not maintenance, and the villagers lacked the resources to repair it. As a result, electricity existed in official records and infrastructure, but not in everyday use, highlighting how one-time provisioning creates the illusion of access while masking ongoing energy deprivation.

When Water Exists, but not When Needed

In the Multidimensional Poverty Index, access to drinking water is measured by whether a safe source is located close to the household. If water is unsafe or takes more than 30 minutes to collect, the household is considered deprived, highlighting health risks and the daily burden, often borne by women and girls, of fetching water.

In the village the authors visited, a water tank was present and a motor pumped water into it, meeting the indicator on paper. Yet on many days the motor stopped working, leaving the tank dry. When this happened, families were forced to walk nearly five kilometres to a nearby lake to collect water.

The indicator counts the tank’s presence as access, but it fails to capture these disruptions and the social hierarchies that shape who actually gets water, when and at what cost. Water exists in infrastructure, but not in people’s daily lives.

When Better Housing Comes at the Cost of Debt

In the Multidimensional Poverty Index, housing quality is judged by the material used for the floor. Homes with mud, clay, or dung floors are considered deprived, while houses with solid flooring are counted as non-deprived, based on assumptions of cleanliness and safety.

In the village the authors visited, one family had taken a loan to build a pucca house. The interest rates ranged between 20 to 50 percent. As Munni (name changed) explained, “For smaller needs, the moneylender gives us Rs 10,000, but we must pay Rs 1,000 every month until we can somehow return the entire amount in one lumpsum.”

These borrowing arrangements trap families in long-term cycles of debt, forcing repeated loans just to manage repayments. While the improved house removes them from the poverty count, the crushing debt that made it possible, and the risk of slipping into generational poverty, remains invisible in the data.

When Assets Exist but Cannot be Used

In the Multidimensional Poverty Index, asset ownership is used as a marker of basic security and participation in social and economic life. Households are considered non-deprived if they own items such as a phone, radio, bicycle, or refrigerator, or have access to motorised transport.

But ownership does not always mean usability. A bicycle provided under a government scheme may be enough to remove a household from the deprivation count, even if it is broken and the family cannot afford to repair it. The indicator records possession, while the inability to actually use the asset, and the limits it places on mobility and livelihoods, remains unseen.

When Financial Inclusion Exists only in Name

India’s expanded Multidimensional Poverty Index includes access to a bank account as an indicator, recognising the role of financial inclusion in economic security and resilience. In theory, bank accounts enable families to save, receive benefits, and manage financial shocks.

In practice, the presence of an account often tells us very little. Many accounts are opened under government schemes but remain empty, unused, or inaccessible.Women, in particular, may have accounts opened in their names without control over withdrawals or decision-making. A household with a zero-balance account is still counted as non-deprived, even though it has no savings to draw on in times of illness, crop failure, or job loss. Once again, the indicator captures formal inclusion, not financial security.

When Poverty Disappears at the Cutoff

In the Multidimensional Poverty Index, poverty is determined using fixed cutoffs. Each of the twelve indicators has a threshold that defines deprivation, and a household is classified as multidimensionally poor only if it is deprived in at least one-third of the weighted indicators. This statistical boundary decides who is counted and who is left out.

Seen through this lens, a family where every member is obese would be classified as non-deprived in health, as their BMI won’t fall in the underweight category. The same family with a bank account but no money in it, an electricity connection without power, an LPG cylinder they cannot afford to refill, a nearby water source that works only a few days a week, and a pucca house built through high-interest debt would still be marked as non-deprived in living standards.

If the children have completed the required years of schooling but gained little learning or skills that can provide them with meaningful employment, the family would also be considered non-deprived in education. On paper, they are not poor. In reality, their lives tell a different story.

As we were leaving the hamlet, a friend made a remark that captured this disconnect perfectly: “If you want to understand health and poverty in a community, don’t look at the data, look at the condition of the dog that lives there.”

Is Poverty Really Declining?

The reported decline in multidimensional poverty has been driven largely by gains in “standard of living” indicators, i.e., access to clean cooking fuel, sanitation, electricity, and bank accounts. These improvements, however, do not necessarily translate into higher purchasing power or greater economic security for households, since each of these gains has been enabled by targeted public policy interventions rather than sustained income growth.

While such policies deserve recognition, it is crucial to remember that these estimates are drawn from the pre-COVID period. Post-pandemic poverty levels remain contested, a debate that can only be resolved through the release of credible and up-to-date data.

Against this backdrop, insights from those working closely with poor communities provide a necessary corrective, one that raises serious questions about how poverty has evolved over the past decade in India. This suggests the need not to abandon multidimensional measures.

The MPI is a valuable step beyond income-based measures, but framing it within Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach can deepen its impact. Sen argues that poverty is fundamentally a lack of capability, i.e., the real freedoms to lead a life one values. Dimensions like health, nutrition, and education are not just indicators; they are essential for building these capabilities.

While income can help access these, structural barriers, such as lack of agency to claim rights or systemic biases based on caste, race, or gender, often prevent people from converting resources into capabilities. Therefore, poverty measurement and policy should address both material deprivations and the social and institutional constraints that limit capability expansion. While the MPI remains valuable for capturing macro-level shifts associated with policy interventions, its interpretation requires caution, particularly in contexts marked by deep structural inequities.

Ultimately, the ease with which such tools can be manipulated forces a deeper question about intent: is the objective to genuinely reduce poverty, or merely to erase it from official view?

(The authors would like to thank Dr Suranjeen Pallipamula for his constructive inputs.)

Edited by Christianez Ratna Kiruba