Trigger Warning: This article discusses intimate partner violence, physical assault, and systemic neglect. Reader discretion is advised.

Blood drips onto the floor. Hands trembling with effort, the doctor passes the needle through the scalp, stitching together the gaping wound on the back of the woman’s head. Unflinching, she lies on the table with glazed eyes, barely registering the pain of the repeated pricks.

After a strenuous 15 minutes, the doctor snaps the gloves off and asks her to come to the emergency desk. Her brother holds her up to stand, as she faces a dehumanizing volley of questions intended to bare the anatomy of the assault.

Sheetal (name changed for confidentiality) is a 46 year old domestic worker. Her husband is a security guard. They have 2 children. They live in an informal settlement at the periphery of the city. The assault took place in their house the same night. The husband was drunk and attacked her with an iron rod in a fit of rage after being refused money for alcohol.

The injuries sustained included blunt object injuries on her back, her legs and a laceration on her head. With clinical precision, these details are elicited and at the end she is asked with a callous nonchalance, “Do you want to file a case against him?”

Analyzing the data: Violence Against Women (VAW)

This nonchalance stems from the systemic apathy to violence against women. While the prevalence of violence against women ranges from 26-31 percent globally, the data in India reflects a much more dire situation. Intimate Partner violence, also known as domestic violence, accounts for a majority of these cases. Outcomes of intimate partner violence range from a risk of physical injuries, unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases to mental health impacts like depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation.

Intimate partner violence poses a complex threat to the health of women and families. Children whose mothers experience violence of any kind - including verbal or psychological- are at a higher risk of developmental and behavioural anomalies, perpetrating similar cycles of violence in adulthood.

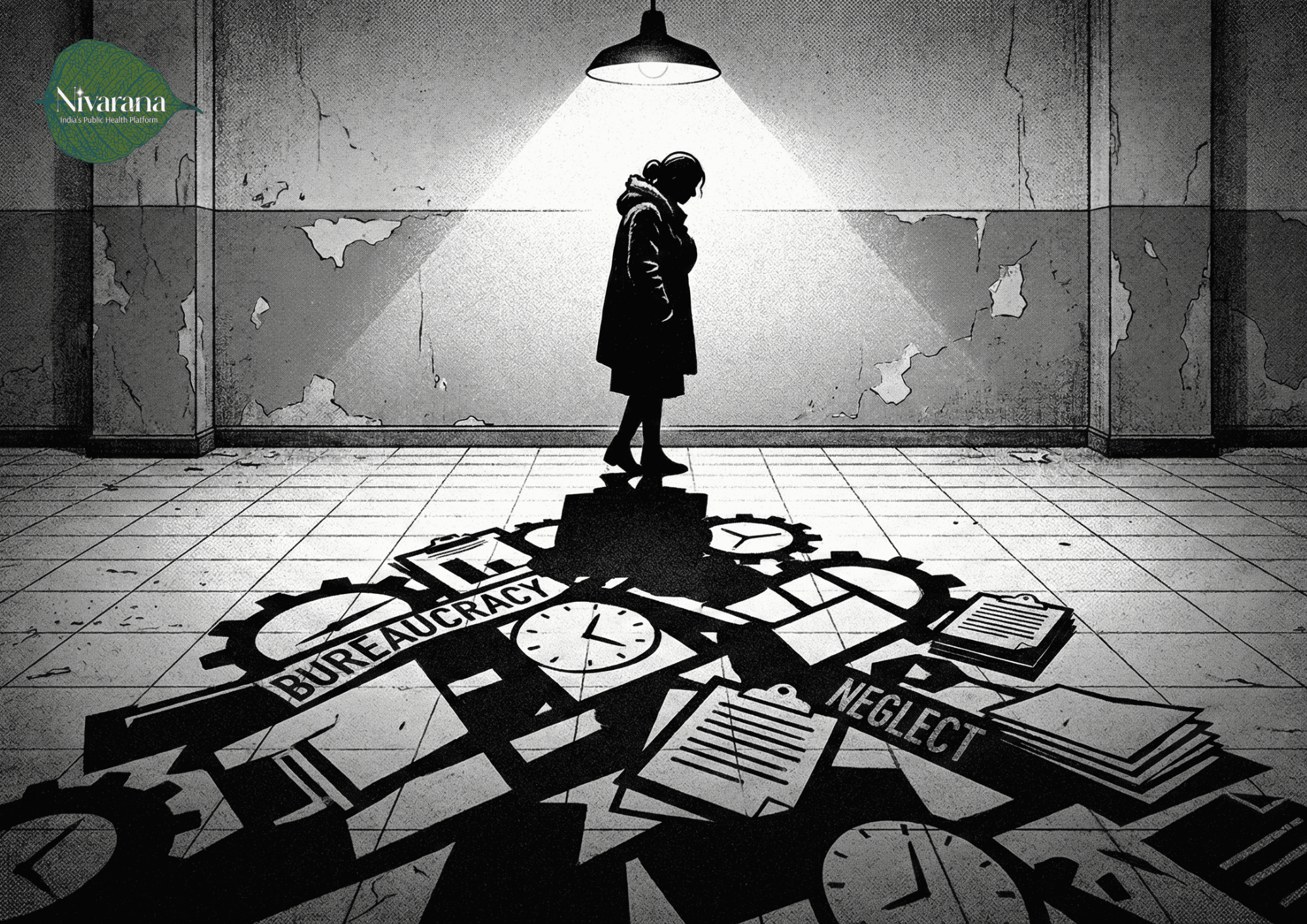

Systemic Gaps in Addressing IPV/GBV

More often than not, the first point of contact between the survivors and the supportive services usually is at a healthcare facility. While violence against women has been recognised as a violation of human rights only as recently as 1993 with the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, India’s own legal instrument in place for IPV was passed in 2005: the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act.

With a strongly jurisdictional approach, the Act highlights the obligation of medical facilities to deliver free and quality care to DV survivors when brought by the police. There is no mention of the protocol to be followed by healthcare providers as the first point of contact of the survivors, neglecting the role played by the health system in intercepting domestic violence.

With women from lower income and class backgrounds significantly affected, most survivors choose not to report violence to the police. The onus often falls on health facilities to initiate and lead humane and supportive responses to such women.

According to the clinical guidelines for responding to IPV and sexual assault (WHO, 2013), beyond ensuring the complete privacy for and confidentiality of the patient, doctors are expected to create a space safe and supportive enough for the patient to disclose their situation without fear of judgement. Additionally, healthcare providers are expected to assist the survivors in accessing legal and psychosocial support.

The guidelines released by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in 2014 include a manual for the Protocols of MedicoLegal Care for survivors of sexual assault. In addition to the role of the healthcare providers as first line medical and psychological support, the protocol presses upon the importance of including details about the role played by the religious and caste identities of perpetrators and the survivors themselves.

Among the many factors driving domestic violence like education, income, place of residence, drinking habits, the role played by caste and religion is prominent. What is especially concerning is the attitudes healthcare professionals unconsciously adopt towards patients from certain caste and religious backgrounds.

This may end up influencing their behaviors, treatment modalities and consequently patient outcomes. Internalising discriminatory attitudes has a two fold impact on worsening the quality of health services while also perpetrating the socioeconomic inequalities embedded within the system.

The National Health Policy 2017 includes violence against women as one of its top priorities. While it mentions the need for capacitation of healthcare workers for sensitive and informed approaches to survivors, there is currently no National Action Plan or Strategy in place to reflect India’s stance on global commitments for the agenda of women’s safety.

Launched in 2015 through the Nirbhaya Fund, a One Stop Centre scheme has been implemented nationwide with the intention of providing comprehensive services and support to women afflicted with violence at home or in public spaces. With 864 functioning OSCs, over 860 crores has been allocated for the scheme since 2015.

While guidelines state the provision of legal, psychosocial and medical support at OSCs, the ground reality usually reflects an absence of coordination between the various limbs of a centre. There have even been reports of the accused being summoned to an OSC to verify the veracity of the claims of assault, leading to a deeply unsafe environment for survivors.

One of the biggest impediments to utilization of the services provided at OSCs is the lack of awareness. Most survivors do not know such centres exist, and the ones who do are unable to access the OSCs, being met with understaffed haunts not providing various aspects of the critical first line support.

Scalable Models from Non Profit Sector

As we try to build a healthcare system more inclusive and sensitive to the needs of survivors of IPV, the non profit sector leads in developing innovative approaches. Survivor centric models like Dilaasa by CEHAT (Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes) have demonstrated immense potential as hospital based scalable models in the context of Lower Middle Income Countries.

Focusing on the capacity building of healthcare providers and the provision of support services through a hospital based crisis intervention department, the Dilaasa model has the following features:

-

Emotional and Psychological Support

-

Legal Support

-

Referral to a shelter as needed

-

An emergency 24 hour shelter within the hospital.

Training sessions were conducted for the staff over a period of 6 months to cultivate a cohort of practitioners that not only were equipped to provide medical treatment but also psychological first aid to the patients while they were referred to the counsellors on site.

ASHAs and Domestic Violence

Society for Women’s Action and Training Initiatives(SWATI), a Gujarat Based NGO, integrated a novel community based approach to tackling GBV. Considering how survivors found it difficult to travel hundreds of kilometres to reach the secondary health centres, around 400 ASHA workers were instead trained to identify women facing violence in the community.

This led to the referral of over 900 women to healthcare facilities for treatment and support. This was projected to help identify abuse in its early stages, with multiple survivors being identified during periods of pregnancy. Educating these women of the impacts of IPV and GBV on maternal health, including miscarriages, preterm labor, low birth weight and increased infant mortality rates, the ASHAs were often even responsible for escorting the survivors to the health care facilities and support centres.

This has led to mounting criticism regarding the increase in their burden of care, particularly when they are already overworked with minimal pay. Moreover, healthcare facilities are often ill-equipped to manage patients presenting with the symptomatology of IPV, making the bottom-up approach involving voluntary health workers unsustainable.

Interestingly enough, the greatest beneficiaries of the SWATI Mahila Sahayta Kendra initiative for community based outreach were the ASHAs themselves. This raises a question about the dangers of laying the responsibility of intercepting IPV on women who themselves are at high risk within their own communities.

Recommendations for Healthcare Facilities and Providers

To bridge the gaps in the system for better health service access among women facing violence, a number of guidelines and recommendations have been released for different levels of health facilities to intercept and manage cases.

At the primary level, the focus should be on capacity building initiatives for gender sensitisation of health workers. Health administrators can build a directory containing locally mapped referral services including relevant names, numbers and addresses of OSCs, Protection Officers, Police Liaisons, legal support, counselling centres. A 24 hour emergency shelter at the hospital for housing the women at risk while they are connected to relevant long term establishments

Secondary and tertiary centres, apart from the above mentioned, need to develop forensic protocols in conjunction with the heads of clinical departments and staff nurses. There is also a need for the incorporation of training in undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

At the individual level, healthcare providers can adopt the LIVES approach for first line support (developed by CEHAT during “Project Uddan”) when interacting with patients: (a) Listen without judgement and with empathy, (b) Inquire about needs, including for medical, social, emotional and financial support, ( c) Validate the survivor by emphasising belief in their narrative, (d) Enhance Safety of the survivor by sheltering them at the facility or if they choose to return to the unsafe environment, by educating them of the various protective measures and (e) Support of all types , legal, psychological, social and medical.

Updating Medical Training and Curriculum

There are multiple reasons for survivors of intimate partner violence choosing not to report their abuse, ranging from stigma to financial dependency. However, another barrier to justice is often presented at healthcare facilities by doctors themselves.

Often we have the victims accompanied by their perpetrators. With no explicitly mentioned protocol in place for privacy of the patients in healthcare facilities, the victims are forced to share the history in front of the assailants. Even in the situations that they come alone, women have reported experiencing dismissal of their experiences and discouragement from doctors from filing a complaint.

Survivors have to endure victim-blaming, disbelief, discriminatory attitudes and in some extreme cases, even refusal of treatment. There is a pressing urgency for the sensitisation of health personnel for a gender sensitive response.

This sensitivity can be inculcated right from the undergraduate level. Despite intimate partner violence being a common presentation in any clinical setting, medical students are not trained at the UG level or even during internship to empathetically interact with patients presenting with such complaints.

While subjects like AETCOM (attitude, ethics and communication) press upon the importance of doctor patient interactions, the communication protocol for survivors of sexual or domestic violence is never explored. The competencies laid out by the NMC in forensic medicine and toxicology fail to include the approach to survivors beyond medical examination. The responsibility of the HCP to provide first line support, mental health support, referral linkages in a safe and confidential space, is never mentioned.

Conclusion

Global trends show a slow and gradual decline over the past decade in intimate partner violence and violence against women. However, healthcare systems continue to fall short. Gaps in essential health services, intersectoral coordination and entrenched biases strip many survivors of not just their health, but also their rights, dignity and agency.

As healthcare providers, maybe it is time for us to take accountability for our own roles and choose a more comprehensive, compassionate and survivor-centric approach.