Between late September and early October 2025, clinicians in Chhindwara, Betul, and surrounding districts reported clusters of previously healthy children coming to them with acute kidney injury and rapid multi‑organ failure.

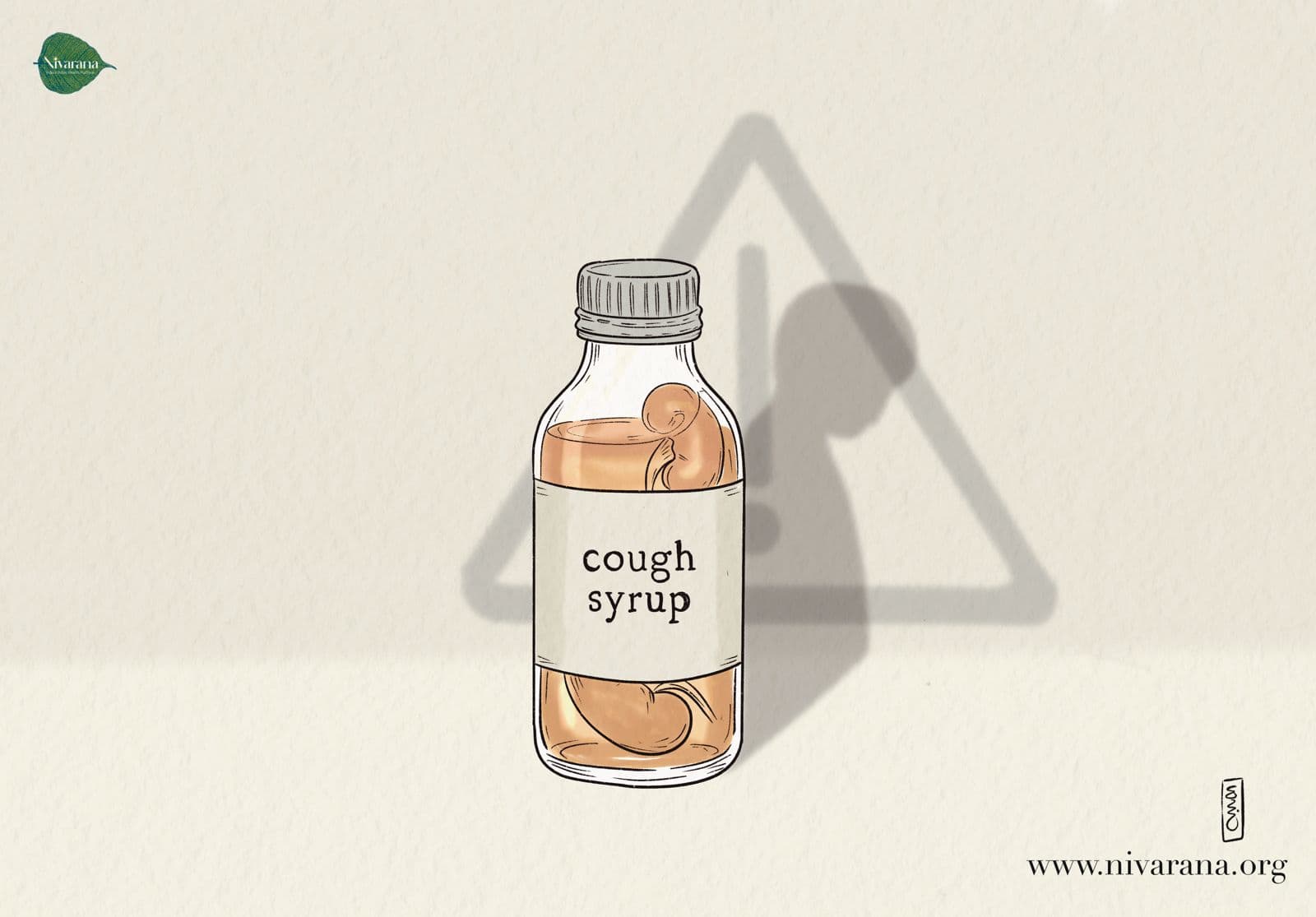

Some clinicians noted that the children who were affected had a common history of having been previously prescribed a cough syrup for cold-like symptoms. After this possible connection was noted, laboratory testing was done by Indian authorities, which identified very high concentrations of diethylene glycol (DEG), a highly toxic industrial solvent in at least one branded cough syrup and traces in others, which the children took before developing these symptoms.

At least 20 children under-five had died by then after taking the syrup, and the manufacturing company's owner was arrested as police and regulators moved to recall affected stock.

As state and national drug controllers ordered product recalls and suspended the implicated manufacturer’s operations while criminal probes proceeded.

And finally, on 9 October 2025, formal reports from Indian authorities confirmed that the same widely used children’s cough syrup was linked to the deaths of children as it contained dangerously high levels of diethylene glycol (DEG).

This epidemiologic pattern of clusters of infants and children progressing rapidly to kidney failure and shutdown of urination is the classic clinical signature of DEG poisoning, which has occurred multiple times in the past through this exact mechanism of contamination of children's medicines.

This report aims to explain the chemistry and medical harms of DEG, trace how contaminated medicines have repeatedly reappeared worldwide, and identify systemic fault lines that allow such tragedies to happen.

What is Diethylene Glycol (DEG) and Why is it Deadly?

Diethylene Glycol(DEG) poisoning usually occurs when someone tries to self-harm by consuming “brake fluid” or when DEG is used as a cheaper alternative solvent in liquid medications, as occurred in Madhya Pradesh.

DEG poisoning typically progresses in three stages. First, a person may experience stomach-related symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, along with serious chemical imbalances in the body. After one to three days, the kidneys may begin to fail, which can be life-threatening without prompt medical treatment.

Five to seven days after exposure, nerve-related problems can develop, including facial paralysis, other central nervous system paralysis, and may be fatal.

All this occurs because DEG gets metabolised in the body to form some toxic substances, such as five HEAA, which leads to acidosis and glycolic acid, which is toxic to the kidneys. Therefore, preventing the formation of these metabolites is the cornerstone of treatment.

There is evidence from animal studies and case reports that the drug Fomepizole prevents the formation of toxic metabolites from DEG, but Fomepizole is not an FDA-approved drug for the treatment of DEG poisoning. Since fomepizole is not widely available in India, DEG poisoning is often treated with ethanol (drinking alcohol), which may or may not work.

The problem of contamination arises because DEG visually appears similar to crude/contaminated glycerin, which is a substance often used as a stabiliser or solvent for various formulations of cough syrups. This leads to the risk of the wrong solvent being used, especially when supply chain controls or testing of batches are inadequate or bypassed.

This is especially worse for children as infants and young children, even small exposures frequently produce severe acute kidney injury (AKI), metabolic acidosis, and multi‑organ failure. Clinical series and toxicology reviews document high case‑fatality rates when dialysis and intensive care are not immediately available.

A Recurring Global Failure with India at the Centre

The Madhya Pradesh deaths sit in a long, preventable lineage of medicine‑contamination disasters. The seminal modern example is the 1937 Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster in the United States, a DEG‑contaminated preparation that killed more than a hundred people and catalysed the 1938 Food Drug and Cosmetic Act. Since then, DEG contamination of medicines has recurred repeatedly across regions and decades.

Most recently, a multi‑country wave in 2022–2023 involved numerous contaminated syrup products and was linked to more than 300 reported pediatric fatalities across several low‑ and middle‑income countries; WHO alerts and clinical reports document clusters in countries including Gambia, Uzbekistan, and Indonesia.

The fatalities in Gambia and Uzbekistan were caused by Indian pharmaceutical companies like Maiden Pharmaceuticals Limited, a Haryana-based company, and Marion, an Uttar Pradesh-based company, respectively, while the Indonesian tragedy was due to their locally manufactured syrups.

Beyond countries with confirmed fatal clusters, WHO alerts have also identified contaminated India-manufactured liquid medicines in markets such as Iraq, underscoring the continued circulation of toxic excipients through global pharmaceutical supply chains even in the absence of formally documented mortality clusters.

|

Year / Period |

Location |

Summary |

Source (Author–Date) |

|

1937 |

United States |

Elixir Sulfanilamide: more than 100 deaths; this event underpinned major US regulatory reform. |

|

|

2008–2009 |

Nigeria |

Clusters of paediatric AKI linked to DEG‑contaminated teething medications and other syrups. |

|

|

2022 |

Gambia, Uzbekistan, Indonesia |

Dozens of children presented with AKI after taking contaminated syrups; high case fatality reported. |

|

|

2025 |

Madhya Pradesh India |

Approximately 20 paediatric deaths reported; cough syrup found to contain very high levels of DEG. |

Where the Fault Lines are

While Indian newspapers reported the deaths, arrests, and regulatory responses following the cough-syrup tragedy, the underlying mechanisms that allow toxic industrial solvents to repeatedly enter paediatric medicines — spanning excipient sourcing, testing failures, and regulatory enforcement — have rarely been examined as a single, systemic failure.

Multiple overlapping system failures exist in India that allow a toxic industrial solvent to reach children's mouths in labelled medicines.

Firstly, the adulteration or contamination of high‑risk excipients by the suppliers, notably glycerin, which is widely used in syrups, can be lethal without batch‑level verification.

Secondly, the inadequate raw‑material and finished‑product testing leads to a key vulnerability that leads to contamination events.

The FDA reviewed recent global DEG/EG contamination incidents and highlighted exactly this problem: "lack of comprehensive identity testing" of raw glycerin (or related excipients), and overreliance on suppliers' certificates rather than independent testing; in many cases, the supply chain origin of the glycerin was opaque or undocumented.

Additionally, regulatory gaps and enforcement shortfalls suggest that laws may exist on paper, but enforcement of inspections, rapid lab testing and traceability is underfunded in many regions.

In its 2025 report, WHO-UNODC signals that contaminated medicines continue to arise because regulatory oversight over excipient manufacturers and distributors remains weak, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The report describes “a lack of regulatory oversight for manufacturers and distributors of high-risk excipients,” and “deficiencies in post-market surveillance and enforcement mechanisms.”

The report highlights intentional criminal substitution of excipients and falsified documentation as not simply mistakes, underscoring that weak regulatory and legal frameworks enable such abuse.

The WHO also alerts note that contaminated syrups are often distributed through unregulated or informal markets, beyond the formal regulatory net, making recalls, tracing, and consumer safety responses extremely difficult.

The WHO/UNODC report explicitly notes how “criminal networks exploit market volatility and regulatory gaps to introduce toxic substitutes” into supply chains, that is cheaper industrial-grade solvents are economically attractive compared to legitimate pharmaceutical-grade excipients when oversight is weak.

Analyses of past poisoning events, such as the 2008–2009 outbreak in Nigeria, show that in some cases manufacturers used “unknown or unapproved raw-material suppliers” and failed to perform identity testing or final-product screening, behavior consistent with cost-cutting or corner-cutting incentive structures that can save producers money in the short term, with catastrophic consequences for consumers.

Together, these fault lines mean a contaminated batch, even from a single bad‑actor firm or supplier, can create a large local crisis and cross borders through informal exports.

The Case for Reform

India is a major global manufacturer of generics and active pharmaceutical ingredients, a critical source for medicines worldwide. That scale is a global public‑health good, but it also concentrates risk: a contaminated excipient or an inadequately controlled small manufacturer can have outsized impacts domestically and abroad.

The 2025 Madhya Pradesh outbreak adds to a string of incidents that have raised questions about domestic screening capacity and supply‑chain traceability, prompting renewed scrutiny from international bodies.

This is not to say India is uniformly negligent. Many reputable Indian manufacturers produce high‑quality medicines for export and domestic use. But the ecosystem also includes a large number of small firms whose compliance varies, which is why independent testing, strong regulatory oversight, and transparent supply‑chain practices are essential.

What Meaningful Reform Looks Like

There are no magic bullets, but practical public‑health gains are within reach if policymakers, regulators, industry, and international organisations act together.

There must be mandatory independent batch testing of high‑risk excipients such as glycerin and finished syrups before products reach the market, with results recorded in a central auditable registry.

Harmonised rapid‑response laboratory networks with accredited methods must be instituted to test for DEG and related contaminants, supported by international partners where domestic capacity is limited . WHO alerts and WHO-UNODC reports emphasize the need for strengthened analytical capacity.

Stronger supplier audits and transparency are needed in the case of excipients. Mandatory traceability using lot numbers, certificates of analysis, supplier registries etc., must be instituted with legal penalties for falsified documentation. The recent WHO/UNODC “Contaminated Medicines” report calls for strengthened oversight of the excipient supply chain, including better regulatory control, supplier verification, and closing documentation gaps that facilitate crime.

Tougher enforcement and legal frameworks that make deliberate adulteration a serious criminal offence, coupled with commercial penalties for negligent quality systems need to be in place.

Public‑health guidance to clinicians and caregivers advising caution with non‑essential cough syrups in young children and emphasising procurement from verified pharmacies and prescribers must be given.

WHO‑led alert systems must be resourced and linked to customs and export monitoring to reduce cross‑border spread of contaminated products. International cooperation is necessary to enforce this.

Criminal investigations and prosecutions are necessary where evidence of deliberate wrongdoing exists, but they are insufficient if they stop at individual actors. Structural failures require systemic reform: regulators must be given the tools and budgets to test, inspect, and trace; manufacturers must be held to transparent standards, and international partners must help strengthen laboratory surveillance, especially in countries with constrained resources.

The families who lost children in Madhya Pradesh deserve more than an apology; they deserve transparency about what went wrong and concrete steps that prevent future tragedies.

Edited by Christianez Ratna Kiruba

Image by Gayatri