Dalli Rajhara, with its streets stained red by iron ore dust, feels frozen in time. A distinct sense of dissonance is sure to occur in the first few minutes of living and breathing in this small town.

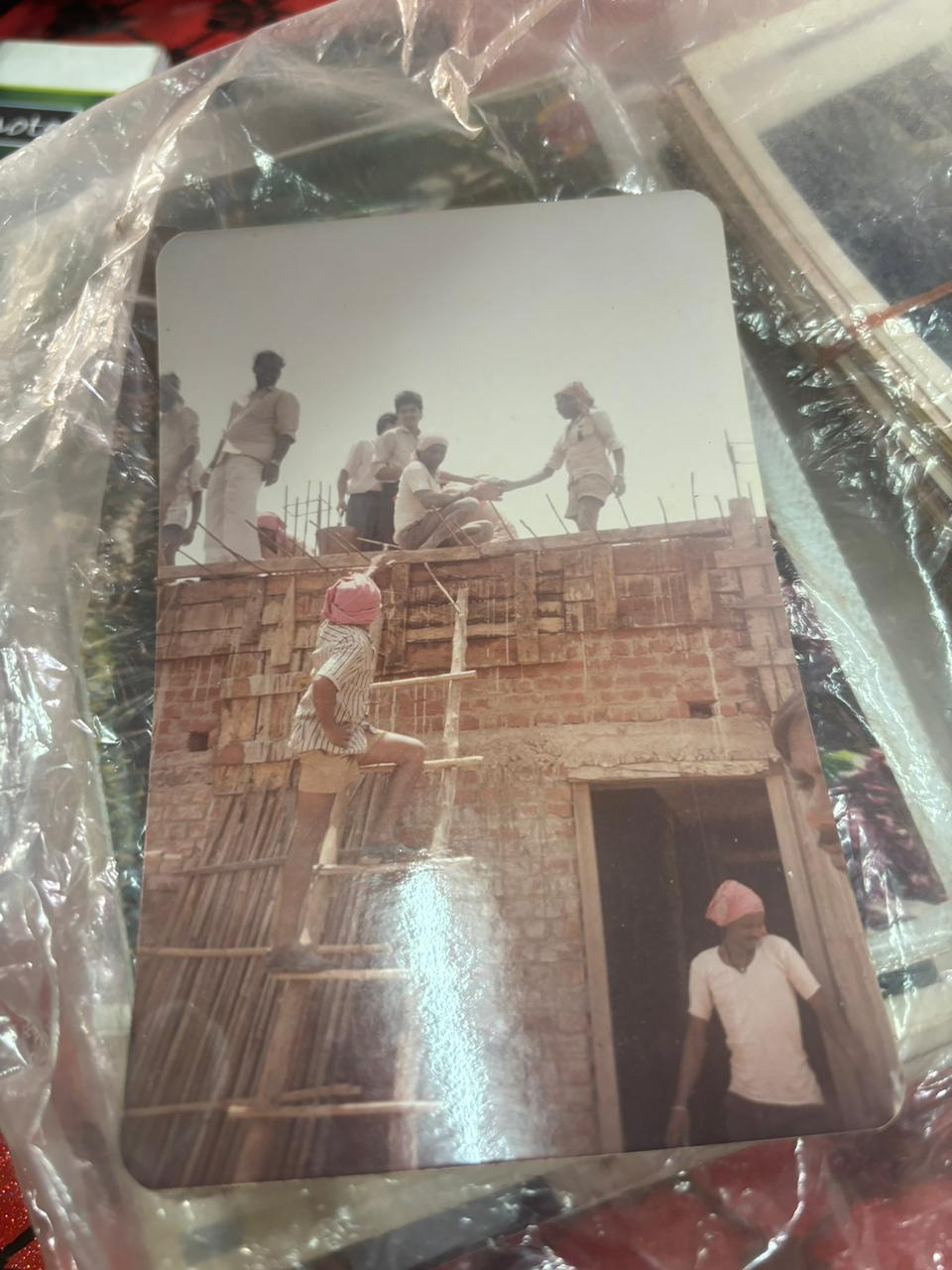

To add to this, the labor movement that has shaped this town for nearly half a century is a story worthy of legends. As a living testament to this history, Shaheed Hospital stands as a reminder of an extraordinary time — built by the workers, and for the workers. Every single brick in the hospital came from the contribution of the workers.

On the stone-plank at the entrance of the old building that commemorates the inauguration of Shaheed Hospital on June 3rd, 1983, is engraved the names Lahaar Singh, mine worker, and Hallalkhor, farmer and a senior villager of Arrejhar - the individuals who opened the hospital.

Dalli and Rajhara are twin captive iron ore units owned by Bhilai Steel Plant, after which the town was named Dalli Rajhara. With a population of around 44,000 (2011 census), it is a small town in Balod district, about 90 kilometres south of Bhilai.

Shaheed Hospital attracts a diverse crowd from the towns and villages as far away as 100 to 150 kilometres. Except on Tuesdays, the outpatient (OP) building and the reception lobby teem with activity on all days of the week. The captive iron ore mines abutting the town, whose history is inextricably connected to this place, observe a holiday on Tuesdays; consequently, Shaheed Hospital also runs with limited services.

On a typical day, the lobby of Shaheed Hospital is thronged with workers, farmers, and small vendors from places like Rajnandgaon, Raipur, Balod, Kanker, Charama, and other places, waiting to be registered.

(Town centre of Dalli Rajhara and the path to the hospital)

From the outside, Shaheed Hospital appears as a merger of newer and older buildings, with sinuous stairs, a spacious lobby, and hallways leading to various sections. Hospital staff diligently move between wards, providing care to the ailing. However, beyond these appearances, the hospital's history is primarily transmitted through casual talk, into which the memory of the struggles is inscribed.

Stories are passed down from lips to ears, from person to person — about the rapid construction of the ceiling, where ten thousand mine workers halted their work to contribute, or the story that involves the denial of electricity to the hospital, which led to a protest of workers from all quarters of mines. These events remain etched in the memories of the hospital's staff and the local community.

(Images from when the hospital was being built by the workers)

Many values churned out from the historical struggles of the workers are seen in the day-to-day conduct of Shaheed Hospital. The hospital is governed by committees and a robust system of internal democracy. Nurses, janitors, doctors, and other staff participate on an equal footing in making decisions on various administrative aspects.

Topics like salaries, work hours, workplace issues, and future activities of the hospital are discussed in the meetings. ‘There’s too much democracy here’, is a whisper I often heard, that the decision-making is too laborious with meandering discussions. However, Shaheed Hospital’s commitment to internal democracy is unwavering.

Jaggu Ram Sahu, fondly called Jaggu Daada, a 70-year-old retired worker in the mines, is generally seen in the hospital in his nondescript pink shirt, greeting the patients and staff alike. He is now a full-time health worker. I once asked him about the history of the hospital. His chest pumped with pride, and sitting at the edge of the seat, he told me about the historic meeting at Lal Maidaan.

The long-felt sense of alienation of the contract mine-workers culminated in the Lal Maidaan protest of 1977. The Internal Emergency had been lifted only three years earlier, and there was an excitement in the air to struggle and to restore the legitimate rights of the workers. ‘In those days, the non-regular workers were making 70 rupees per month, while the salary of regular workers was 300 rupees’, recalled Jaggu Dada, ‘even though we were technically doing the same work’.

Jaggu Daada speaks with a glitter in his eyes about the vibrant days of the Lal Maidan protest. He remembers that thousands of contract workers stayed there for many days, and danced, sang, and talked about organising and unionising. They were demanding bonuses, compensations for enforced idleness at work sites, and pre-monsoon allowances for the repair of their mud huts.

(Jaggu Dada in his characteristic pink shirt)

The Lal Maidaan protest metamorphosed into Chhattisgarh Mines Shramik Sangh (CMSS), the trade union that chose Shankar Guha Niyogi, who was well known as a union organiser and activist at that time, as its leader. When I asked Jaggu Daada how they discovered Shankar Guha Niyogi and how they decided that he would be their leader, he said with a smile, "How do you know of Nelson Mandela, and decided to respect him, in the same manner, we knew of Niyogi ji by that time and chose him to be our leader.’

Illina Sen, a rights based activist and academic, who was closely associated with the trade union movement of Dalli Rajhara writes in her memoir ‘Inside Chhattisgarh - A Political Memoir’: “Shortly after the new union was formed in 1977, its leadership paid a visit to the nearby Danitola mines, where Shankar Guha Niyogi was recuperating at his sasural (wife’s parental home) after being released from detention under the draconian and dreaded Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA).” It was here that the union leadership, aware of Niyogi’s work and ideas, pleaded with him to take charge of the intellectual and organisational growth of the workers’ movement.

The movement was life-changing for many people like Jaggu Daada. His desire to help people made him gravitate towards the Swasthya Vibhag (health department), one of the 17 departments chalked out by the workers’ organisation. Shaheed Hospital was an initiative of the Swasthya Vibhag. The hospital was named after the martyrdom of 11 mine-workers who were killed in the police firing of 1977, which took place after the historic Lal Maidaan meeting.

Jaggu Daada started off as a voluntary health worker in 1981, during the days of the makeshift clinic that began in the mud-hut garage of the trade union office. Alongside working in the mines during the daytime until his retirement in 2012, he continued to be a voluntary health worker - the job he’s passionate about. After retirement, he has become a full-time health worker. He even took extended leaves to join Shaheed Hospital’s health teams in responding to disasters like the Bhopal Gas Tragedy and the 1993 Latur earthquake — actions that caused his superiors to raise their eyebrows.

For Jaggu Daada, activism and health work are closely interconnected. When I asked him about ‘Sangarsh aur Nirmaan’ - Struggle and Build, a principle propounded by Shankar Guha Niyogi, he said, ‘We fight for our stomachs, and we work in the hospital for the society’ with a smile.

Narratives like Jaggu Daada’s keep repeating amongst the seniors of the Shaheed Hospital.

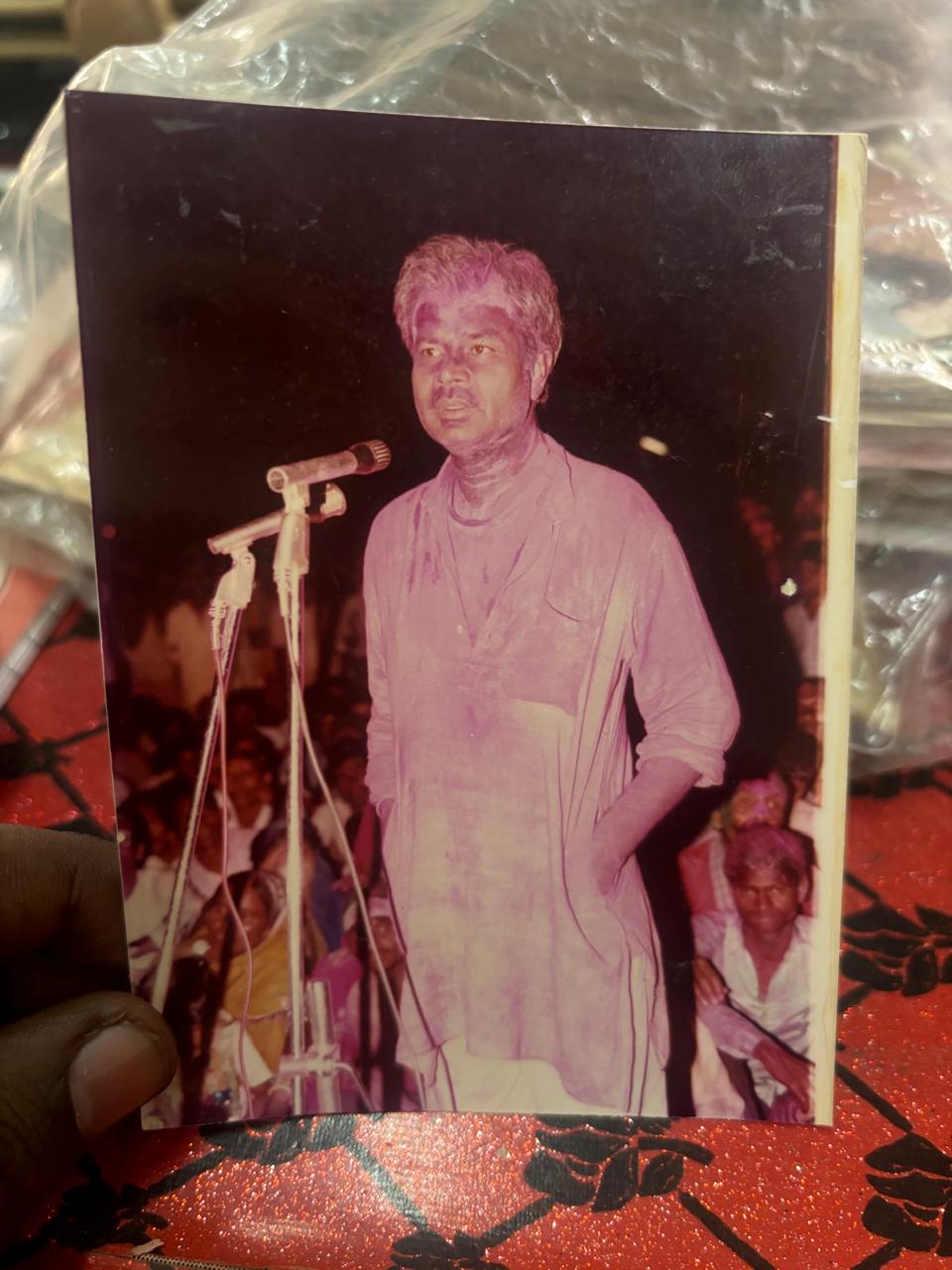

(Photo of Shankar Guha Niyogi from the Shaheed Hospital photo album)

Kuleshwari Deedi — Kuleshwari Sonwani, the most senior of all nurses currently working, recounted her story to me. ‘I don’t have an identity without Shaheed Hospital’, she told me. She is one of the nurses who stayed with the hospital from the time it was a makeshift clinic in the garage of the trade union office.

When I asked her about how the Shaheed Hospital that stands today came about, she told me the story of Kusumbai. ‘Kusumbai, one of the worker-leaders, died while giving birth, due to a lack of a medical facility. The doctors at BSP health facility in Dalli Rajhara denied her admission since she didn’t possess a health card. At the mourning meeting of Kusumbai’s, the workers decided to build a hospital for themselves, and for others in similar situations,’ she recounted.

Until Shaheed Hospital came to be, the healthcare of the contract mine-workers in Dalli Rajhara was non-existent, as they didn’t have any perks or entitlements as regular workers did. The determination of the workers to build their own hospital was complemented by many young doctors like Binayak Sen, Ashish Kundu, Pabitro Guha, Saibal Jana, Punyabrat Goon, etc, who stood in solidarity with the workers in realising the collective dream of a workers' hospital.

(Kuleshwari Deedi, first row, rightmost)

Kuleshwari Deedi, a 69-year-old veteran, faced many personal struggles in her journey. Her husband was dead set against her working at Shaheed Hospital. Back in the day, the woman who went out for work was called characterless, she told me. “He was a raging alcoholic — he would return home late at night, and beat me,” she said, about her husband.

At times, out of suspicion, he would even sleep in the hospital on her night duties. Many times, she sought refuge in the hospital, fleeing her abusive home. Her husband squandered all the money on alcohol. The echoes of her husband's drunken rage still lingered in her memory. “Just thinking about those days gives me a jolt,” she said.

At that time, when her family deserted her and no one stood by her side, it was the doctors and staff in the hospital who supported her in every way. ‘I don’t think I would have survived all this long without this hospital,’ she said, her eyes becoming tearful. She had two sons and one daughter. One son died by suicide. As time went by, and Kuleshwari Deedi’s kids became older, the power dynamics at home tilted in her favour.

Over four decades, a mere mud-hut dispensary gave rise to the sprawling hospital that stands today. However, the early years of Shaheed Hospital were rife with challenges. Sujatha Deedi, another veteran nurse who retired recently, recalled the beginning days of the hospital with vivid details.

At that time, there was very little money to hire professional staff. Workers interested in health work were recruited as volunteers to run the hospital. In her memoir, Illina Sen writes about how David Werner’s Where There Is No Doctor had formed the basic text for the health workers' training. As many workers had limited formal education, discussions and graphical representations were used to convey information, along with theory and practical classes with doctors.

In the same manner, Sujatha Deedi was called to start working at the clinic-dispensary after a trade-union meeting. ‘It was a time of immense multi-tasking. Besides nursing duties, we were fetching water from great distances, washing clothes, cooking, and taking care of the clinic.’ She recalled the days of plastering the former mud-walls of the hospital with a mixture of cow dung and mud.

In the early days, the entire staff, including doctors, nurses, and health workers, formed a tight-knit community. They lived together, sharing meals cooked by themselves. Even the doctors and nurses pitched in, washing hospital bed sheets. ‘We rarely left the hospital,’ she recalled. "We worked long hours, from 11 AM to 12 PM. And initially, we weren't paid. We were just helping our neighbours,’ she said.

Now, a 150-bed hospital with wards for Surgery, General Medicine, and Obstetrics & Gynaecology, the hospital grew on the shoulders of the nurses, janitors, health workers, trade union activists, communist doctors, labourers, and farmers of the region. Its charges are minimal to suit the incomes of the people here. The administration is largely run by the leaders of the trade union and the staff in the hospital. About 200 patients visit Shaheed Hospital’s OPD on a daily basis.

All this phenomenal work has an unflinching backbone in the form of a 70-year-old chief medical officer, Dr Saibal Jana, fondly called as Jana sir. He is the powerhouse that anchors the workflow in Shaheed Hospital.

For the past 40 years, Dr Jana held the hospital together, committing himself to the egalitarian values of the workers' struggles. A stocky gentleman with hearty laughter and boundless energy, he is often found during clinical rounds, clad in a simple cotton kurta or shirt. His eyes, behind the flat-rimmed spectacles, scan each patient with intense focus. As one doctor told me, ‘Jana sir insists on keenly observing the faces of patients. According to him, one can arrive at a broad probable diagnosis just by looking at the face, in many cases.’

Through constant self-learning, he became a doctor capable of treating all medical and surgical needs the people of this region would need. As the leader of Shaheed Hospital, he spearheaded the people’s health movement that campaigned against various health-related issues affecting the workers in the region.

From the construction of the building to the training of the health workers, he was involved in all the phases of the hospital’s development. From speaking about the billionaires at the operation table while repairing a hernia, to actively subverting the narratives of Big Pharma on concepts like ‘health’ and ‘treatment’ during routine clinical rounds, Dr Jana is the moral compass of Shaheed Hospital.

(Dr Saibal Jana in rounds)

While taking clinical rounds, he once said, echoing trade union leader Shankar Guha Niyogi's concept of 'semi-mechanization,' 'If machines err, we may never know. But if humans make mistakes, there's always room for correction.' ‘Semi-mechanisation’ is an important idea for our times of artificial intelligence and technological revolutions, and its re-articulation is due. It evolved from a campaign of CMSS against full-mechanisation that would displace many jobs in the mines.

At that time, Niyogi argued that ‘full mechanisation was not the desired technology option for a labour-surplus country such as India, and that a better strategy for the Dalli Rajhara mines in the future was ‘semi-mechanisation’. CMSS also commissioned a study on semi-mechanisation in mining, with a research team consisting of economists from Delhi. Illina Sen writes about their report in her memoirs, “Their report commended this option and showed that, cost-wise, semi-mechanisation was cheaper, besides being labour-friendly”.

In a similar spirit, Dr Jana gives primacy to human observations over a machine’s results. Relying on thorough clinical examination instead of excessive testing can help patients avoid unnecessary healthcare costs. In a different instance, Dr Jana said, ‘We need to apply our consciousness in the process of production. The ones who want to promote machines are the ones who prioritise profits over humanitarian values. A machine’s parts should be replenished every so often, and that itself is capital-intensive.’

He continued, ‘Ultimately, it is the human consciousness that is key to arriving at conclusions.’ This is a step towards empowering the science of people over capital-intensive technology. In many ways, Dr Jana’s words encapsulate the core value of Shaheed Hospital.

At Shaheed Hospital, whispers become winds. Branch to branch and mountain to mountain, an echo travels from labyrinthine caverns of mechanised mines - into the environs of the hospital where infants are born.

The echo: it’s a roar to mobilise, upturn, rise, revolt, and liberate.

Edited by Christianez Ratna Kiruba

Image by Gayatri